In December 2023, I wrote about the state of human-machine translation as we headed towards 2024. The technological march of machine translation had dominated 2023. From personal musings over the last twenty years, comparing my professional situation with 12 months before, for the first time in 2022 and 2023 my outlook was a more pessimistic one in consecutive years.

My view was one of human translators being pushed towards fighting for scraps at dumping MTPE rates. More were considering moving away from translation or increasing their other activities than moving towards focussing solely on translation. In house, I had started to receive editing and revision requests that “didn’t seem quite right”. They seemed more fluent than their authors’ previous drafted texts, but also weren’t quite factually correct. In other cases, the inconsistency of terminology shone through. The sinking feeling was that my own descent towards MTPE drudgery had begun. The profession shared my pessimistic outlook. The fragility of (self-)employment relationships, needs for efficiency and cost-cutting amid difficult financial times were also apparent.

2025: a turbulent start

When I started sketching out this article in mid-December 2024, I didn’t know how 2025 would begin in terms of technological announcements. DeepSeek was not on the radar – by the end of January it was everywhere. Possibly from a translation professional’s perspective the most interesting aspect was OpenAI’s complaint in late January that new upstart DeepSeek was using “its” data. That’s right, the same data that OpenAI itself had unashamedly scraped to train itself. Excuse me Mr. Altman while I locate the sub-atomic-sized Stradivarius.

In recent weeks, I’ve read a number of people saying that this could be positive for easing OpenAI’s (perceived?) monopoly. For many, ChatGPT has become a metonym for AI. Others think it could herald a torrent of new solutions – some fear one that might finally be able to translate (impacting their endangered volume of translation work and pushing them further towards MTPE’s clutches). And that was before the latest development of Elon Musk expressing his wish to buy OpenAI.

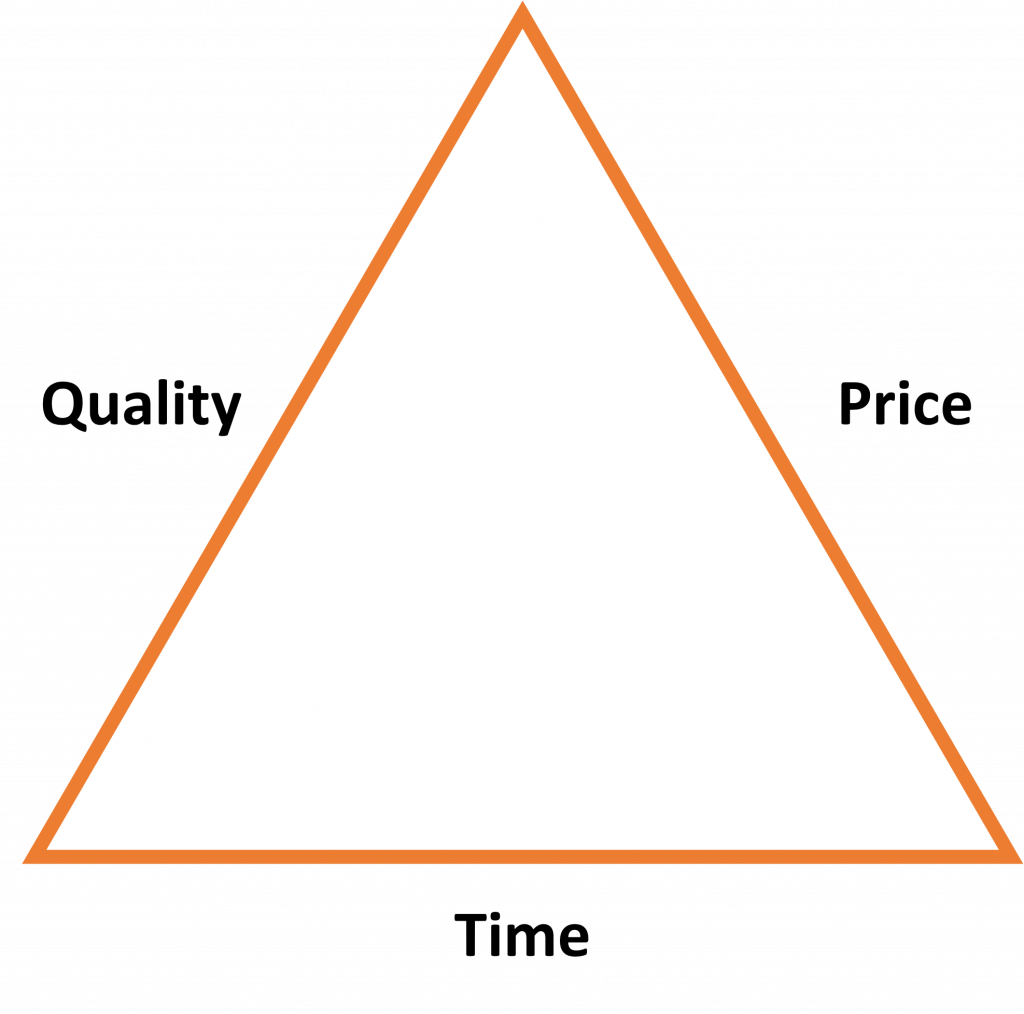

The schism between the translation industry and the translation profession

The trend of recent years of a divergence in approaches between the translation industry and the translation profession continues. It had been a pandemic edition of the Translating Europe Forum (TEF) that first pushed the Human in the Loop (HITL) agenda. At first sight, its deceptive allure took me in. Over time, I became aware of the weasliness of the term “Human in the Loop” for translation. HITL is misused: it fails to define the expertise level of the human, and does not advocate the human retaining control/leadership. The industry seems to be revising its estimation somewhat with new term “Human at the Core” which is closer to my “Expert in the Lead” approach than “Machine in the Loop”, but is still coined by the industry. My “Expert in the Lead” concept is also about coming down on the side of the profession over the industry.

Fresh hope from the industry?

A piece from late in 2024 by Arle Lommel for CSA did give me some hope that the industry is also coming round to the fact that HITL will not sustain human translators in the human-machine translation era. One remark in that piece captures why HITL gets it wrong, and how that “janitorial role” of HITL will not be fulfilling.

“[…] “human in the loop” models – a sort of window dressing for post-editing – … often relegate expert linguists to an essentially janitorial role, sweeping up “bad MT” (quality checking and correction) and cleaning up AI messes. Instead, CSA Research has shifted to describing augmented translation as “human at the core” because, at the end of the day, empowered linguists will be making the decisions, aided by technology.”

The Language Sector Slowdown: A Multifaceted Outlook, Arle Lommel for CSA Research

Looking back to my assessment in December 2023, I opened with the following paragraph:

The debate about the future of (human) translation and changing role of translators is the biggest topic in translator circles. 2023 has been the year of the (unstoppable?) march of machine translation. Within a year of bursting onto the scene as an unknown, OpenAI’s chatbot, ChatGPT, can apparently also translate. Human translators increasingly face tighter, more competitive markets. Many are not even consulted about their replacement by MT solutions, but maybe grudgingly offered MTPE work. And there are talks of tightened budgets and gloomy outlooks of recession. So are the days of out-and-out translators numbered?

Michael Bailey, transl8r.eu blogpost – December 2023 – Who’s in/on the lead as we head into 2024?

As I prepared to write this post, I asked fellow professionals over LinkedIn how they viewed the situation. A modest little poll on LinkedIn among my network of fellow translators returned a slightly blurry snapshot. I asked pretty much the same question as I have been asking myself over two decades. From over 80 responses, less than one quarter of responses viewed their situation more optimistically. In contrast, 45% view their situation more pessimistically, and the remaining third see it as unchanged from the previous year. From those responses, a number of in-house translators and specialists in less common language pairs seemed more optimistic. Of the positively inclined, many were offering premium services with a narrow specialist focus. A few reported that new areas of specialism had emerged that compensated for the slowdown in business in other areas.

Busy-ness and Business

Some responses mentioned improved levels of “busy-ness”, but qualified the improvement being due to time-consuming customer acquisition drives. For others, new services and specialist areas had arrested the slump, but hadn’t banished doubts about the long-term future. In a few cases, new revenue streams opened up from (re)activating new language pairs, although a number I connected with did not realistically view adding further language combinations as a potential solution. Others viewed that the situation was no worse than a year ago, but had also not improved. For some of these this kind of struggle was a “new normal” – the glass was neither half-full nor half-empty.

Of those viewing the situation more pessimistically, several commented about an acceleration in the shift towards MTPE from “pure” translation work. Many freelancers lamented that their “valuable and valid” contribution was unable to outweigh their customers seeking “value for money”. By value for money – they mentioned diminishing rates (whether by line, character or page) or more MTPE work. A couple also said that work from major agency clients drying up had impacted them. In other cases the agencies had shifted towards an MTPE-based model instead of “classical translation”. Some others mentioned that reorganisations and mergers had meant that major customers had already reviewed the situation. A couple of respondents mentioned that smaller companies had been absorbed into larger groups with in-house language services.

Payment Practices

One contact also said that their pessimism was fuelled by longer payment times, although still within the agreed timeframe – a potential sign of agencies also suffering from cashflow issues. Amid ongoing cost of living issues (price inflation outstripping wage/salary increases, or downward pressure on rates), the financial squeeze becomes more apparent.

By delaying this post, I wanted to also allow myself the opportunity to catch-up with the first swathe of “Monthly Recap” posts on LinkedIn in 2025, in addition to “year-end round-up” posts. I’ve come to appreciate that it has been a busy month if I don’t have time to even consider writing one. However, this is where internal time and performance tracking negates a need for such a round-up. In 2024, H2 showed a remarkable up-tick: in May, based on figures until the end of April, translation time was around 73% of productive hours. By year-end it was up above 80%. In addition, my worked hours were higher for translation in 2024 than total hours for 2023.

How do you feel about the security/future of your role as a human translator, compared with 12 months ago?

These figures are why I see the security/future of my role more optimistically going into 2025. But this might be due to the short-termism of recent successes masking and negating struggles earlier in the year. Looking back at the reasons behind my pessimism in the last two years, uncertainty weighed strongly on my mind. Transformation and reorganisation bring uncertainty and insecurity. As a digital transformation programme started, I had felt marginalised and sidelined. And I felt that remit creep was also disruptive for my “course” as a translator. So while doubts existed, along with the simmering AI hype, I remained pessimistic. Learning about a suggested roll-out of MT without harnessing our language data probably fed the pessimism. So what changed so much in twelve months for me to enter 2025 with renewed optimism?

Getting back to business

In previous years, the non-translation-based tasks I was logging increased. I advocate that 100% efficiency/productivity is an illusion, as is 100% productivity as a translator. However, translators are susceptible to worrying about a dilution of their time spent translating. At year-end 2023, my productivity tracking showed I was translating for less than 80% of my hours. When I started the job, the level was closer to 90%. I felt a need to arrest the drift towards my knowledge-based job becoming a non-translation-based one. So I enlisted the services of a coach, and focused on using my mid-year appraisal to shed some non-core commitments. It was a timely reboot, and boosted my translator’s esteem. Esteem is so important.

Translating for a predominantly “non-public” domain means that a lot of my work’s impact never reaches the outside world. Internal visibility is therefore very important. Fortunately, the second half of 2024 served up a plethora of demanding, substantial and internally visible jobs. As a translator I still feel happiest translating, although I can use non-translation tasks to draw breath. I’ve learned to fuel my internal visibility. I am most visible where my translation results in the desired supervisory outcome at short notice. Internal visibility also builds momentum, as has been the case going into 2025.

A public or private persona

As wonderful as a very private persona sounds for less gregarious translators, I nevertheless need to maintain a public presence. Presentations and publications (e.g. in the ITI Bulletin and Universitas Mitteilungsblatt) also bolster the public impact of my work as a translator. The workshop I gave in Spiez and the contacts gained there were crucial in a lot of self-esteem issues. Three days’ reflection proved a turning point for “getting back to being me” and to steer out of the doldrums of silo-thinking. As I put the final touches to this piece, in 2025 I already have three further presentations confirmed, a conference participation and other irons in the fire.

In silo-like environments, especially for the “lone rangers”, i.e. SPLSU in-housers like me or freelancers who do not work together with other translators in virtual teams, social media can become an ersatz barometer of success and a way to shout from the rooftops. The problem is that the algorithms can suck you in, but don’t pay the bills. Add the peacocking influencers to the equation and they will tell you to post hourly/daily/weekly to feed the algorithm. However, my work’s confidential nature means that I can’t get sucked in by the siren-like call of the algorithms. I don’t have the fear of missing out that a freelancer has, if they don’t take on a piece of work. And much of the messages are about the successes – after all you project success far more than failure.

How are others feeling?

From some of the end-of-year posts I read, some professionals certainly put in the hard yards and enjoyed exceptional years (in terms of acclaim and remuneration) in 2024. To them: congratulations – your messages show that there plenty of life in professional translation. From viewing their profiles and websites, they all specialise in certain language combinations and with some very interesting niches. The common key to their success also seems to have been their efforts in fresh customer acquisition and keeping customers.

Some found that new areas of specialisation were opening up: either related to their existing areas or fresh new areas. Others pleasingly reported old customers feared lost returning to them after a dalliance with the AI/MT “good enough” world. For every success story, however, there were also stories of people having lost customers and work drying up. In some cases there were cases of agencies folding owing translators money. One such case was the bankruptcy of WCS Group and the agencies it ran (subsequently bought by Powerling). Many freelancers were left out of pocket. As I added to this post in mid-January 2025, there was a new twist to the Powerling story: The Dutch Society of Translators has just expelled Powerling from being a member. (h/t to Loek van Koeten for this information).

Upskilling and job crafting for survival?

Before I was able to actually narrow my remit, I had had to consider upskilling (i.e. obtaining alternative skills to complement my skills as a translator) and even put my foot in the water in actively pursuing courses to be fit for the new world of human-machine translation. However, obtaining new and possibly diametrically opposed skills to those I already possess as a translator proved counterproductive. Instead, with new areas of supervision coming online, my focus has now reverted to deepening my breadth of knowledge in the subject areas I cover. Some translation professionals have echoed this: those who will survive already possess all the skills and specialisations to survive.

Teaching old dogs new tricks?

Regarding the prospects of who will survive the AI deluge, I’ve read numerous estimates about the proportion of translators who will “survive” the AI revolution, with many stating between 10 and 25% percent, although the range is far wider. Part of the issue also relates to the stage of their career that translators are at. As William Lise identified in a blog post of his, some are close enough to retirement, and others young enough to change position. However, there is a substantial group of translators, particularly mid-career ones, trapped by the roots they have put down.

Whether people who have retrained from other professions are any safer is hard to tell. They may bring expertise from a past career, but may lack the translation experience. Possibly being newer in the “trade” might work both ways: be more firmly tied to making it work as the cost of retraining hasn’t been recouped yet, or in contrast, not so firmly embedded in the profession that they can’t “get out”. From a number of contacts who always viewed translation as a “safe Plan B”, they’ve changed their minds about wanting to commit to it.

Expertise counters AI hype

Nonetheless, the reality after the tidal wave of AI hype has proven that expertise remains essential – accountability and credibility of translations are areas where human translators still have an advantage. AI and NMT flushes out generalists working for agencies and pseudo-specialists. In this case, broad fields of specialisation (e.g. financial/legal) for agencies maybe stops people from standing out from the crowd. Others say they experience agency work decided upon purely by means of “fastest finger first” – an issue I mentioned when I blogged about the profession/industry schism in autumn 2023. In that case, expertise is unlikely to be given a chance to shine through.

In contrast, genuine specialists in narrow fields remain an elusively rare commodity. Regarding AI, there is a healthy scepticism about how it can really be a substitute for expertise and experience. Simply throwing more scraped data at the problem isn’t the solution, particularly as synthetic language data now swamps the originally lush large language pastures trained on human generated language. In this regard there is a counter revolution of some boutique LSPs looking for high-end translators whose personal service commands premium rates. In a couple of cases, some freelancers have even reported that they have profited from customers turning to them due to unsatisfactory agency experiences, viewing them as a “perfect fit” after lacklustre past experience.

And when the boot is on the other foot?

Occasionally, I outsource work to freelancers. The objective remains to ensure the desired supervisory outcome. This also sheds a lot of light on the “black box of translation”, market practices and how solid briefs helps so much. I have come to get a good feeling whether translators 1) want the job and 2) feel they can do justice to the job in hand. Genuine experts seem less fazed in not being able to take a job on. I also admire their honesty. Such a situation might be vastly different than dealing with an agency, where selling and margins are everything. The requirement of a satisfactory outcome, allows me to use a best bidder approach, rather than a cheapest bidder one.

Capitalising on AI’s vulnerabilities

Amidst the OpenAI/DeepSeek saga, I used the opportunity to highlight the accountability, control and expertise that expert human translation offers that AI and MT cannot. When “data scraping” allegations surfaced, I chose to capitalise on highlighting data confidentiality. My approach for the aficionados who brazenly claim how much time their ChatGPT Pro subscription saves, is to ask how they feel prompting techniques have changed, robustness of sources, and their views about the size of the context window.

The disarming tactic is to speak the fanboy’s language rather than coming across as too protectionist. Only then do you highlight the issues that impact your translation work, and therefore confirm why your expertise is required (e.g. in a zero/low-resource language combination, with high demands on confidentiality, and the necessary to avoid hallucinations).

Changing job remits

In terms of job creation, I’ve observed a tendency towards not replacing departing staff, or at best retaining existing headcount. New translator jobs are seldom. Looking at job descriptions, may advertised positions have been for maternity cover positions, often initially limited to a year. It can easily take a year to get to grips with new procedures, practices and subject areas. Other vacancies have more of a project manager/coordinator role emerging rather than a “translator” remit.

Monitoring open opportunities (I receive them through mailing lists from professional associations) is useful for gauging remit shift/creep. Job descriptions have clearly changed. Jobs creation rather than replenishment occurs in the area of LangTech. New LangTech units in larger language services are in-housing expertise. From conversations with people fitting the new profile, many highlight prominent “sponsors” within the organisation and strong links to IT being behind the creation of the new position.

Managing language data has definitely become more than a “rainy day” activity – as has terminology work. In a small language services unit, terminologists were traditionally considered a luxury. With the advent of Machine Translation, robust terminology has gained in importance. Machine translation-generated texts into German have demonstrated why I need terminology for all locales of German. My recent work has really brought home the differences between Swiss/German/Liechtenstein/Austrian banking terminology.

Driven loopy – the expert/machine/human in the loop/lead.

As previously mentioned, the very strong industry-led approach to human-machine translation is of “machine in the loop” and “human in the loop”. The industry’s financial and PR clout dictates the way translation (both as an industry and a profession) moves forward. However, industry-led perspectives focus on leveraging technology to an extent where human involvement is negligible or a poorly-paid afterthought.

This is quite apparent from the shift in the industry from humans predominantly “translating” to “post-editing”. In some cases the actual level of human expertise in the post-editing stage is questionable. Pitiful rates fail to motivate a professional: low per word rates for MTPE require unrealistic output levels to earn enough. It would take raw output pretty close to publishable in the first place that you can simply sign off. However, this realistically only works where translation is only required to be “good enough”. And the long-term job satisfaction of this approach is also negligible.

The HITL narrative is pushed so far that the MITL approach barely gets a look in. Rebranding translators as “language experts” is a mere sop. In much the way that the electorate in the UK may/may not have “had enough of experts”. “Language experts” is just another weaselly term: genuine expertise may often be found in far narrower areas or a single source-target language combination. Imagine the (justified) outrage if we were to rebrand microbiologists or astrophysicists as “science experts”.

Throw more language data at it?

The fact is that amid Messrs. Altman et al. scraping the Internet for content to build their LLMs, human generated language data has been exhausted. Tech bros continue to recite their “more data = better results” mantra. The synthetic data has already flooded the Internet, creating new “reheated” synthetic language data. All that changes here is the consistency of the turgid porridge.

The “more data = better results” approach is like a juggernaut or steamroller, or raging waters trying to pass through a pipe of a certain diameter. Upgrading pipes might permit a greater volume of waters to flow, but unless done end-to-end the flood risk still exists.

Many AI companies are still a long way from break-even let alone posting profits. This raises ethical questions. Why should we allow tech companies to break human knowledge-based industries, accelerate climate change, only to line the pockets of the super rich, if they ever turn a profit? Industry dictates the terms: amid skewed arguments of increased efficiency, knowledge-based work is still fraught with “hallucinations”. Why should translators tolerate such hallucinations?

Resistance is (not) futile?

My view about the Expert in the Lead results from my conviction that the role of the human in human-machine translation remains essential. I do concede that the days of “human translation” from the formative days of my career are gone. Instead, rather than resist the use of technology, the emphasis has shifted to ensuring human expertise remains in control. For me, this involves making the smart choice about the use of technology, rather than rejecting it. Experts in human-machine translation can resist by refusing to have their workflows dictated to them. Refusing to be a cog in the process keeps them in the lead rather than in the loop.

My bespoke service revolves around my correctly blending multiple translation memories (setting those penalties in relation to age of TUs, subject matter, incorrect locale/language variation) and really knowing what the translation is about. At the same time I also can make a sound decision about the sources of reference material to access. This has far better chances for meaningful and fruitful success, than the drudge of cleaning out the stochastic parrot’s sodden cage from an LLM prone to hallucination.