It has been a busy few weeks. My project and process management experience have been put to the test in a different manner. I had to process large volumes of machine translations for subsequent access in an offline data room as part of an inspection mission. Extensive use of raw machine translation was the only possible approach: the quantities of translations required for gisting purposes vastly exceeded available internal and external human translation capacity. In some cases required documents could not be machine translated for various reasons. I would have suggested that “pigs might fly” if anyone had suggested anything to the contrary.

As I have mentioned elsewhere, in some instances, there was also the risk that raw MT output could result in creating unnecessary downstream workload. Fortunately, such unnecessary work was widely avoided by means of effective but sparing use of human translation. Human translation often provided clarity where raw MT output could not. The exercise also proved useful in providing insights about non-translators’ perception of translation. It reinforced my understanding of the reality for consumers of translation.

This post addresses several points left unanswered in my first “7 thoughts” piece in January 2025.

- Translation remains a blackbox for many non-linguists: their sole interest is a passable output their input. They are not interested in the procedural steps, particularly the obscure ones that assist in ensuring quality. However, issues do surface about the rendering of key terms. This opens up discussions on the need for terminology. The issue has surfaced in my M365 Copilot Champions training. In our icebreaker “speed-dating” sessions with other champions many said they use Copilot to translate. I’d usually follow-up and take them up on issues encountered: the issue of inconsistent terminology leached out.

- Having machine translation on tap, seemingly at no charge, can make people wasteful of resources: “seemingly limitless” amounts of capacity available for machine translation meant inflated amounts of translation, than had only human translation capacity been available. Similarly, as meetings expand to fill time slots, no limits on submissions mean that people are less disciplined in the amount of files they request for translation. We lose sight of what is truly essential. In some cases submissions were entire electronic files (with 100s of files and 1000s of pages). I added notes about existing human translations that I supplied as an oversight mechanism. This sometimes elicited surprise: people were unaware of translations’ existence. I’ve taken this away as feedback for the future regarding marketing my output internally.

- “Good enough” is really all some people are after: in some cases, a raw machine translation exceeds the requesting party’s own capacity for a “translation”. Logically, such users will embrace machine translation in this case as the default option. Seductive fluency of Modern NMT and LLM/GenAI-based systems also reinforces their satisfaction with the output. Similarly, there is greater tolerance in terms of expectations for MT output over human translation. This issue demonstrates what the translation profession is up against: it is difficult for some to charge premium rates for a time-consuming process, where near instanteous raw MT output apparently “satisfies” their need.

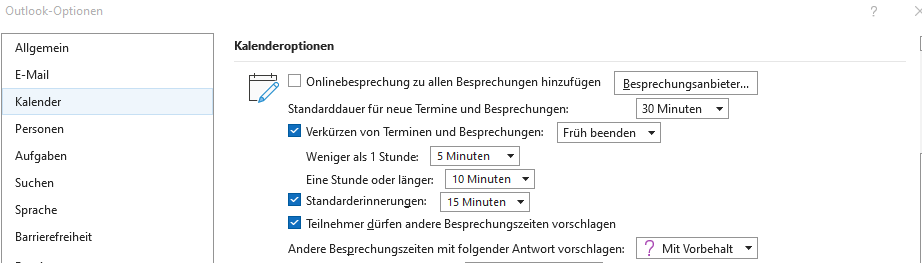

- MTPE has a different cognitive load to human translation: I took care when setting out my stall. I chose to centralised rather than delegate handling the documents. By centralising the task, I had a full set of documents in case I needed them. I chose not to look at the raw MT output: it was available on a strictly “as is” basis. This was the only possible option: checking them would have resulted in the need to knock them into shape. That was not my task. Indeed, I would probably have struggled to have found a happy medium in post-editing. Inconsistent terminology would quickly have become an annoyance. And I needed a strategy to do this extra task while not affecting my own working processes, to cement that I work as the expert in the lead and remain firmly in the driving seat. I would not want to suddenly be the passenger, a “human in the loop” in the translation meaning. I became ruthless: discovering limits on daily limits on numbers of documents, size of files, numbers of files, Translating 1,000s of files, while not losing my own translation time was essential. I’d fed batches of files to translate while I was eating lunch, in a call, or waiting for seminars to begin.

- The advantage of centralising the process with a translator: given that machine translation is such a black box, a translator needs to maintain an oversight or even override role. In the worst case, I knew how the machine translation had been conducted (i.e. engine/model used, source format etc.) In the case of a poor translation, I also wanted the option to run the source text through the MT engine and have a bilingual XLIFF or TMX output as a starting point for a re-translation, without needing to align the text myself. This was also essential for ensuring the strict segregation of human and machine translation. Also this meant that I had to receive source texts, to avoid being inundated with with target texts with no source text, e.g. texts of GenAI produced output to correct.

- The grey zone about internal reliance on machine translation is greater than previously realised: NMT and GenAI have increased staff members’ general awareness of solutions like DeepL (put on a pedestal over Google Translate). The same can be said of the putative ability of GenAI/LLMs to translate. This awareness leads to far more “grey” machine translation than thought. Staff members will use any available solution unless it is physically blocked. Some institutions will actively block tools like Grammarly due to security risks entailed by using it. The same is true for LLMs/GenAI. Until a company blocks access to ChatGPT or DeepSeek etc. staff members will still use them. Merely having rules prohibiting such solutions is not a sufficient deterent.

- Effective outcome-based human translation and poor raw MT output can reinforce people’s confidence in human translation: despite seductive fluency, and “passable” quality and speed of delivery and availability, the value of human translation can shine through when the output really matters. People still value knowing they can rely on a translation. Some jobs remain too sensitive for MT despite mitigation measures taken. The human touch also shines through subtly. In one case I had to translate two iterations of a presentation (i.e. to show the progress made on a project).

I translated the files together (using a virtual merge). This helped ensure the consistency of terminology, which helped guide discussions. MT struggles to be as consistent (e.g. repeated segments inconsistently translated across documents). Then I added a personal touch – I added a “virtual sticky note” to the cover slides to provide a reference to the abbreviations used. By eliminating the guesswork for the reader, it also impressed that this was a human translation from the outset.

How did I go about it:

I took a calculated approach to avoid unnecessary cognitive downstreaming to me.

- I did quick checks for all received folders for standardised documents with only differing content (e.g. a reused template). In certain cases I made template legend available as a human translation in addition to raw MT.

- On occasions I translated lists e.g. of process names. In preparing the translation, I chose an approach to prioritise maximising meaning over concision – and to ensure that related documents also used these process names – to help improve coherence across many documents.

- I prioritised document requests arising from meetings for human translation, and highlighted that they were provided as human translations rather than MT.

- I explained internal jargon (e.g. names of certain committees, working groups, names of soft law instruments) – e.g. using the virtual sticky note.

- I prioritised some brief softlaw instruments for translation and publication, thereby increasing the permanence of the translation, in contrast to Raw MT for “here and now”.

- I set up workflows to allow quick alignment of MT and separate read only TMs for MT output, to avoid MT translation contaminating working TMs, while also providing a starting point for human translation.

- I used feedback requests from specialist divisions to add terminology, and locate documents prioritised for future translation, revision and checking by subject matter experts and publication.

Turning the process into a pipeline for ongoing translation:

The successful conclusion to the mission should not be the end of the story. There is another mission ahead. In this regard, the next steps are:

- Giving contributors and coordinators the chance to find out what went well, and what we could try to improve.

- Adding a chapter to my language services handbook (LaSH) based on the learnings from the feedback.

- Prioritising a list of translations for publication prior to the next mission.

- Process optimisation

- ensuring documents for translation are saved separately and not embedded in other files.

- Nomenclature rules for filenames (including limiting length of filenames.)

- Handling of large files (e.g. chunking to reduce waiting time or uploading for translation during breaks etc.)